Photograph of a portrait by G F Watts of Lord Russell.

Since first appearing in Russell Lights on the 16 September 2004, Heritage Corner has enlightened readers about Russell’s unique and considerable history. For its 100th Heritage Corner article we thank Russell Realty for their continued support and revisit the beginnings of our town, Russell.

When Governor Hobson was looking for a site for a temporary capital in 1840, he chose Okiato in the Bay of Islands. Purchasing the land from James Reddy Clendon, who was running a trading station there, he renamed the place “Russell”. New Zealand’s first capital had a short life, as a second capital was founded when Hobson removed to Auckland in March 1841. In January 1844, Russell’s boundaries were extended to include Kororareka and “His Excellency the Governor” directed that Kororareka be henceforth designated by the said name of Russell.” Russell” of today was Kororareka of yesterday.

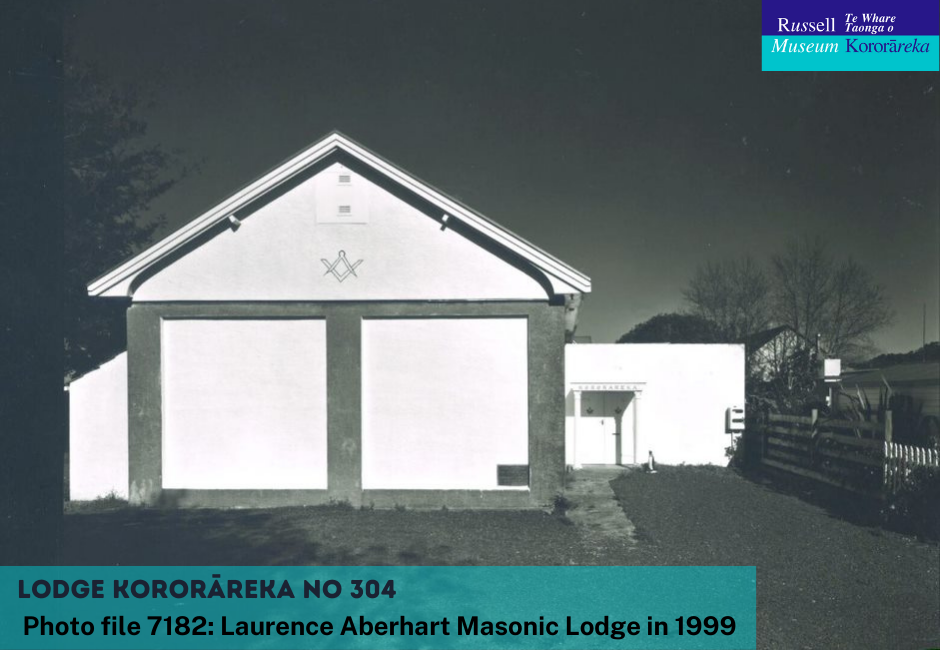

Russell was named in honour of Lord John Russell who was Britain’s Colonial Secretary at the time. The younger son of the sixth Duke of Bedford, although not in line to inherit his father’s vast land holdings and family estates, was entitled to a seat in the House of Commons. Politics became his calling. A Whig, Lord John Russell went on to become Prime Minister of Great Britain twice, once in 1846-52 and later in 1865-66. He was created Earl Russell in 1861.

It was in 1844 when Lord John Russell served as Colonial Secretary that the town adopted his name although it never was the capital, as many people claim that it was.